Still Standing After All These Years

Part 12: Glendale Police Enforcement 1914 - 1915; Expansion and Tragedy; First Officer Killed in Line of Duty

By Katherine Peters Yamada, August 2024.

Photos from Glendale History Room unless otherwise noted.

In 1914, just a few days after our second police chief, George Herald, was appointed, a new police and fire station opened on East Broadway (at the site of the current main post office). It included a jail and a courtroom for the judge. Firemen monitored the jail’s occupants. With the new chief and the new building came an expansion of record keeping, as noted by Captain Mike Post, retired, author of ‘Pictorial History, Glendale Police Department 1851-1990.’

1914 Police Force

Police personnel on duty in late 1914 included:

George H. Herald, Fire Chief/Marshal;

E. A. Laurence, Badge #1;

C. V. Arrington, Badge #2;

H. M. Miller, Badge #3;

E. A. Schroder, Badge #4.

Smaller "Special Police" badges were issued to

H. Lankford

George T. Brewster

W. Burton

Captain Stanley

C. E. Hall

Dr. T. C. Young

Ed Kinser

To what, possibly questionable, use these "special badges" were put is not known, Post wrote; however, the next 30 years saw a liberal unregulated use of police badges for many purposes, mostly political, in all police agencies in the area.

1914, First Official Records

The first efforts at formal recordkeeping began in 1914:

At 8:20 p.m. on February 7, 1914, two men, C. Broggs and Tony Escorse, asked the chief for "Hoboes Lodging."

Later that night a residential burglary was reported, the first crime of the month.

Two days later, at 11:30 p.m., a suspect known only as Maloney was charged with intoxication and disturbing the peace. "Mahoney resisted to the last minute. (Officer) Everett's arm hurt in scuffle putting him in cell, was very noisy good part of the night."

“Some of the comments in the record book certainly reflect a different era in police work. Physical and ethnic descriptions of suspects would make any modem chief cringe.” One "disturbing the peace" suspect was described as "insane on religion we think." A La Crescenta man was arrested and fined $10 for "walking recklessly."

Kids riding their bikes on the sidewalk had their bikes impounded for a week.

Most vagrants were arrested and then "floated out of town," presumably involving transportation beyond the city limits. “Dozens made such trips during 1914.”

W. M. Moore, a "drug fiend in bad shape," was involuntarily committed to County Hospital, typically a two-year "cure." Gilbert Perrez, charged with a violation of Section 8 of the State Poison law, "Raising Indian Hemp commonly known as Marijuana," received a suspended $150 fine.

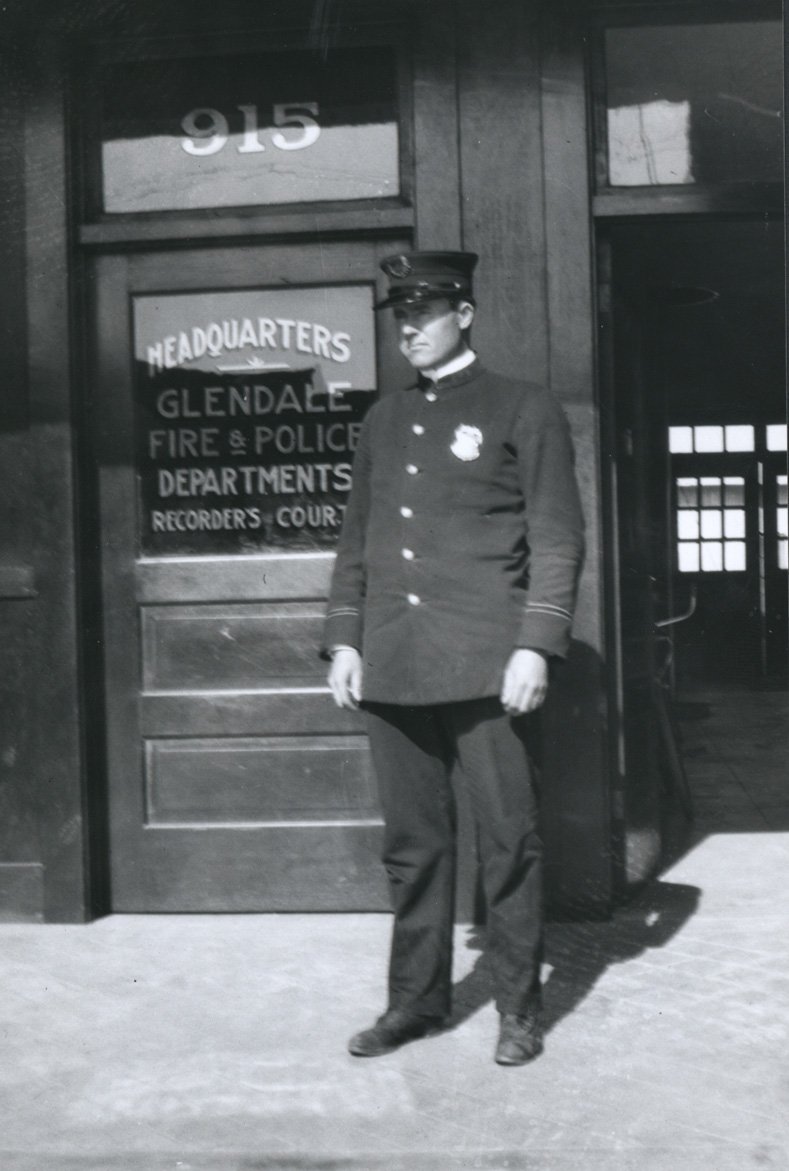

Officer in front of Fire and Police Headquarters, on Broadway

Meet Charles Whitney Smith of Tropico

Born in upstate New York in 1872, Smith soon headed for California. There he met Mae Gibson, who lived with her family in Riverside. They married in 1906 and resided in Riverside. In 1912, the couple purchased a house on Boynton Street in the small town of Tropico, at the southern border with Glendale. Tropico was the first stop on the Southern Pacific Railroad line north out of Los Angeles. Established in 1887 on the old Rancho Santa Eulalia, it had incorporated just the year before and had its own city hall and police and fire services.

Smith Appointed City Marshal in 1914

At first, Smith worked as a clerk for the San Pedro, Los Angeles and Salt Lake Railway, which ran along Glendale Avenue. He joined the Tropico Voters’ Club and became known for his work ethic and tenacity. Mae Smith was a teacher, according to a Tropico city directory. In 1914, Smith was appointed city marshal, as well as the city’s building and plumbing inspector and also served as an acting board commissioner as needed. He worked out of the new Tropico City Hall, built on the southwest corner of Brand Blvd. and Tropico (later that street was renamed Los Feliz).

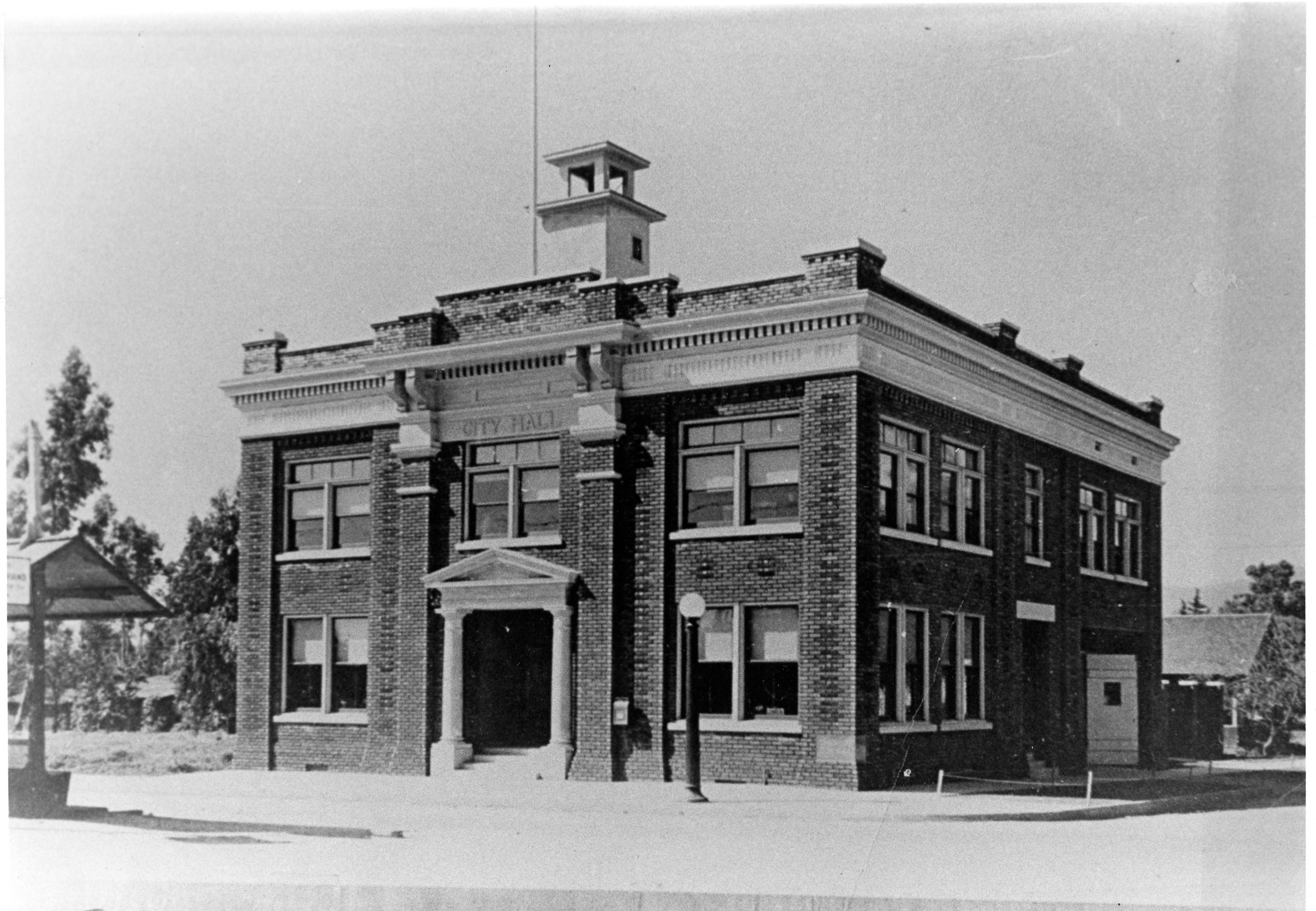

Tropico residents had approved a $25,000 bond in 1912 and the building was completed in October of 1914. The first floor of the brick building held a lobby, a public library, the city clerk’s office and an engine room for the fire department. The second floor held an auditorium, the jail and justice court, plus committee rooms.

Tropico City Hall, built 1914

Map showing original Glendale and Tropico. Credit: Teal Metts

Officer Smith . Credit: Teal Metts

Officers Killed in Line of Duty

In 1914, the town marshals of both Burbank and San Fernando were shot to death in the line of duty. When Burbank Marshal Luther Colson was shot near the railroad tracks that ran through that town, Smith joined the manhunt, along with 25 deputies and many volunteers.

By early January, Smith’s busy schedule often kept him away from the police station. Tropico’s Board of Trustees were concerned by this and called a Saturday meeting to request that he resign. His friends later told newspaper reporters that “It was his persistency in patrolling the entire city that kept him away from the station.” Smith went home to Mae, who urged him to give up his star and the position he valued so much. But he refused, telling her, “No I can’t do it. I am giving Tropico the best there is in me and before I quit my position, I am going to show that I am more than worthy of my hire.”

That evening, Smith walked to work at the Tropico Jail, inside City Hall. Meanwhile, a man named Stephen A. Haviland headed for work at Munson Drug Store on San Fernando Rd. Near the Presbyterian Church at Central and Laurel, two men with guns robbed him of $3 in silver, his gold watch and a gold stick pin. Haviland quickly reported this to the police, just a block away.

As Tropico’s only law enforcement officer, Smith headed out - alone - and found the men sitting on a curb, apparently waiting to escape by streetcar. Neither resisted when he placed them under arrest and began escorting them, on foot and apparently unrestrained, to the jail. Suddenly one suspect, later identified as Gilbert Herringa, broke away. Smith and the other man, William Zylstra, continued to the jail.

After locking up Zylstra, Smith, following a hunch that Herringa would board a streetcar headed for LA, walked along the rail tracks on Glendale Blvd. towards the Atwater Station. On the way, he met up with three GPD officers, Marshal Herald and Officers Frank Farr and Claire V. Arrington, who had learned of the incident and offered their assistance.

Smith continued walking south on Glendale Blvd, crossing the Los Angeles River on the old bridge that then spanned the river.

When Smith reached the Ivanhoe substation, it was about 8:15 p.m. There, he boarded a streetcar that was ready to depart and immediately noticed a man resembling Herringa seated near the front. As they headed south toward Klondike Park, the neighborhood between the Ivanhoe and Elysian Heights stops, Smith moved up and sat next to the man, engaging him in conversation in order to confirm that it was indeed Herringa.

Witnesses later told a Los Angeles Times reporter that the marshal suddenly stood up. Seeing this, Herringa pulled out a .44 caliber revolver, firing four shots. He jumped from the moving streetcar and fled in the darkness to Klondike Park. The streetcar driver rushed Smith to the 6th Street station, four blocks east of City Receiving Hospital. When his wife heard the news, she went to the hospital by motorcar, arriving as the doctors were still attempting to save him. Although he could hardly talk, he reportedly whispered to her, “Maybe I made good tonight.”

Manhunt

As word spread, every available man joined the hunt for Herringa. LA County Sheriff John Cline and 15 deputies set out for Klondike Park. Herald and his officers headed for the Tropico jail to ‘grill’ Zylstra, who identified Herringa as his partner and gave the location of their rooming house at 320 Crocker Street in LA.

Shortly after midnight, four LAPD police officers set out for Crocker Street. As they approached, they saw Herringa through an open window. Noticing their approach, Herringa fired his gun, nearly striking Fitzgerald, and turned off the lights. The officers called out for him to give himself up. Hearing no response, the detectives returned fire and heard him scream. They forced entry and fired again as Herringa ran towards a rear porch. He died instantly. Police determined that the two men were responsible for numerous crimes within the past four months, making off with $5,000 in cash. Haviland’s gold watch was found in Herringa’s pocket.

Residents of Tropico and Glendale were shocked by the tragic death of the 42-year-old man who had been named marshal just 9 months before. His body was taken to Scovern, Letton and Frey Mortuary at 120 Cypress Street in Tropico. The rector of St. Mark’s Episcopal Church presided over funeral services and Tropico businesses closed so storeowners could attend.

Six Tropico firemen served as pallbearers. They accompanied his casket to Forest Lawn, established in 1906, followed by hundreds of residents and friends. Mae moved in with her sister’s family in Los Angeles and remained there until her own passing at age 76. She was buried next to her husband in 1954.

PE Railway Map, ca, 1950. Credit: Netty Carr

Tropico and Glendale Pacific Electric Streetcar, Los Angles, ca 1915. Credit: Teal Metts

Tropico Merges With Glendale

Tropico had incorporated in 1911, but the small town wasn’t large enough to maintain its streets and sewers and other functions. Many residents wanted to join a larger city and in 1917, after talks with the cities of Los Angeles and Glendale, 514 of Tropico’s 1,548 voters voted to consolidate with Glendale. The official acquisition took place on January 8, 1918, coincidentally, three years after Smith’s murder.

Still Standing After All These Years

As Glendale’s Police Historian and Museum curator, Teal Metts wanted to learn more about Marshal Smith. On the 109th anniversary of Smith’s death, Metts embarked on a hunt for his grave in order to pay his respects. He walked the oldest section of Forest Lawn, checking the location markers, but could not find Smith’s grave. He went to the office to verify that he had the correct coordinates, Section C, Lot 80, Space 12, and searched again before realizing that his grave had no marker.

Knowing that Smith had no children and no next-of-kin, Metts wondered if the GPD or city officials could erect a marker. Before contacting Forest Lawn to make the request, he began an intensive search for what happened the night of January 9, 1915.

He visited the Hall of Justice in Los Angeles, meeting with his friend, LA County Sheriff Museum staff member Deputy Mike Fratantoni. There he viewed a 1915 logbook: entry #56, listing the inquest date and cause of death of Herringa. Just a few pages later, entry #59, Los Angeles County Coroner Calvin Hartwell had entered Smith’s cause of death. “Gunshot wound of the lungs. Homicide.”

Metts uncovered more details through digital searches of several sites, including multiple newspaper accounts. The January 11, 1915 LA Times showed the only known images of Smith, Herringa and Zylstra. Metts obtained Pacific Electric records to determine where the long-defunct streetcars had once stopped. He walked the “Corralitas Red Car Trail,’ remnants of the tracks which once ran along the hillside portion of the route, noting that the shooting took place near the intersection of Riverside and Fletcher drives.

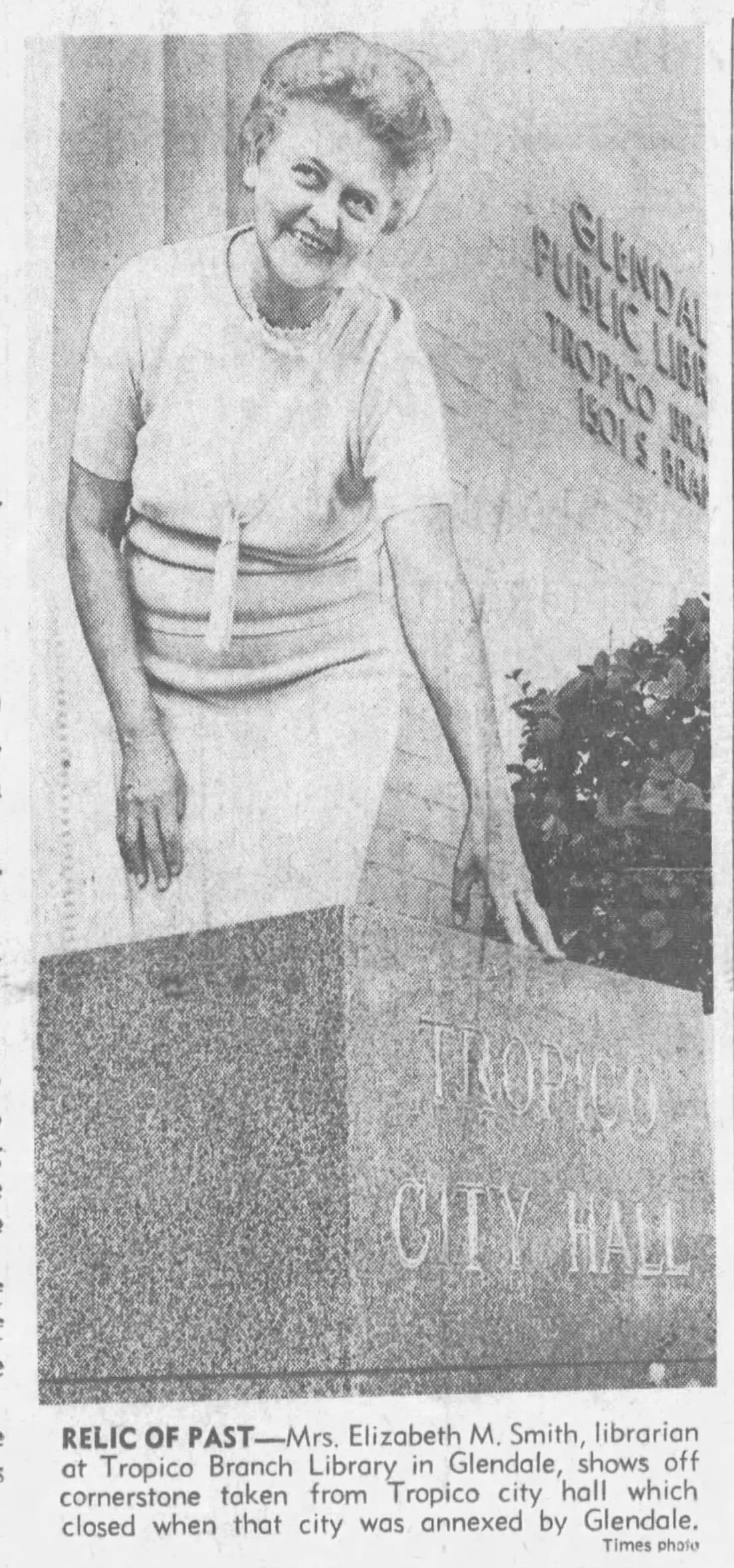

He also visited several buildings important to Tropico history and to Smith’s short tenure as marshal. When Glendale absorbed Tropico, their City Hall closed and services were merged with Glendale. However, the library, on the first floor, remained open as the Tropico Branch Library. In the mid-1940s, the old city hall building was demolished, and replaced by a library/fire station complex. The city hall’s cornerstone was displayed in front of the new library.

Later the library portion became the headquarters of the Glendale / Crescenta Valley Chapter of the American Red Cross. The fire station was vacated in 1988 when Fire Station 22 relocated to Glendale and Palmer. Both the former fire station and the former library appear to be vacant as of this writing. According to Tropico historian, Netty Carr, the city hall cornerstone is now at Fire Station 22, just left of the flagpole at 1201 S. Glendale Avenue.

Tropico Marker. Credit: KPYamada

Cornerstone, Tropico City Hall. Credit: KPYamada

With his research complete, Metts approached Forest Lawn officials with a plan to fundraise for a grave marker. Cemetery officials delved into their own archives and determined that Mae Smith had purchased both sites after her husband’s death and that she was buried in Space 11. Cemetery officials offered to provide a marker for her and waive ‘setting’ fees for both.

With Forest Lawn’s generous offer in hand, Metts sent out fundraising emails within police department and retiree circles. Six hours after the initial outreach, he had surpassed his goal of raising $3500.

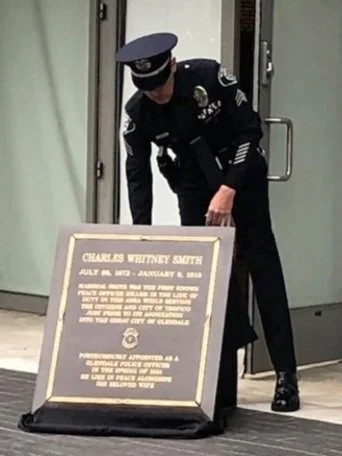

While designing a marker for Smith, Metts realized he didn’t know what kind of badge Smith had worn. After a visit to the archives in the Atwater Village Library (which inherited much of Tropico’s historical items), he approached GPD Police Chief Manuel Cid and suggested posthumously appointing Smith as a Glendale Police Officer. The chief quickly agreed.

The Memorial

In May 2024, an annual memorial ceremony on the steps of GPD headquarters paid tribute to the brave officers who had sacrificed their lives in the line of duty. Smith’s newly cast marker was unveiled and displayed along with the 1915 Glendale Police and L.A. County Coroner logbooks. Later that morning, Smith’s marker was taken to Forest Lawn and placed next to his wife’s marker. A reminder, according to Metts, that honoring the memory of those who have fallen in the line of duty is an ongoing commitment and with the hopes that “Marshal Smith’s story will continue to inspire and resonate with future generations.”

GPD Officers at Smith’s burial site. Credit: Teal Metts

Elizabeth M. Smith, Tropico Branch Librarian with cornerstone, ca. early 1940s

Former fire station 22 and library, 2024. Credit: Teal Metts

Fire Station 22. Credit: KPYamada

Teal Metts unveils Smith’s grave marker. Credit: KPYamada

Credit: KPYamada

Resources

The Glendale History Room, on the second floor of the Central Library, has city directories dating back to 1906, photographs of early Glendale, and archival collections on the Glendale Unified School District, Forest Lawn, theaters of Glendale and other Glendale-related topics. Visits are by appointment only (please email glendalehistoryroom@glendaleca.gov)

Our local history was studied extensively by early historians, including John Calvin Sherer, who authored ‘History of Glendale and Vicinity’ in 1922. Carroll W. Parcher incorporated much of that information in `Glendale Community Book,’ published in 1957. A later version, ‘Glendale Area History,’ was published in 1974 and expanded in 1981. Unless otherwise noted, much of what is included here is from these books and from “Glendale, A Pictorial History.”

Other Resources

“Pictorial History, Glendale Police Department 1851-1990,” by Captain Mike Post, retired

“Charles Whitney Smith, Tropico Marshal,” by Teal K. Metts

“Images of America, Atwater Village,” Netty Carr, Sandra Caravella, Luis Lopez, Ann Lawson